How does the old rhyme go? To market, to market, to buy a fat pig. Home again, home again, jiggety-jig.

A few generations ago, “go-to-market” meant loading your livestock onto a wagon and setting out for the nearest town square.

Times have changed, of course. Go-to-market now has its own discipline, its own strategic consultants and its own acronym (GTM). Let’s take a look at some of the major successful VC and entrepreneur voices in the industry to get an idea of the different approaches to go to market (and get back home again, jiggety-jig).

What is go-to-market? (the one sentence definition)

Go-to-market is how you bring a product to its first customers. (Just making sure we’re on the same page here: Now we can move on.)

What should you go-to-market with?

If you were selling fat pigs, you’d go with a fat pig.

If you’re selling a mobile app, however, or SaaS, or even an online course that will teach users how to cook eggs like nobody’s business, you don’t have to have your finished, polished product in hand before going to market.

Let’s take a look at three different expert approaches on what to go-to-market with.

Approach 1: MVP & MVE (Minimum Viable Product or Experience)

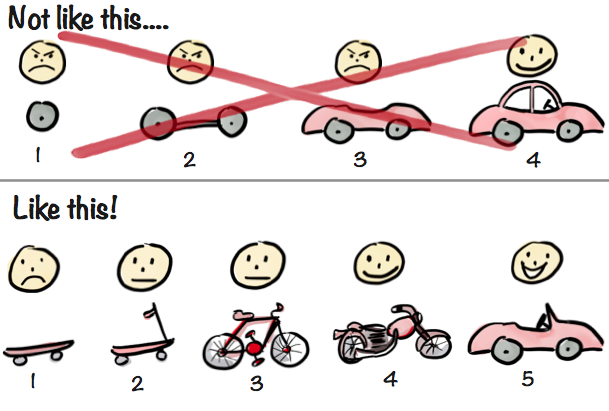

The MVP has gotten a lot of press. It’s been popularized through approaches like Eric Ries’ Lean Startup and variations thereof - and that popularity is often well-deserved. Henrik Kniberg drew and wrote about the original MVP comic that’s since gone viral:

Source: Henrik Kniberg

Peter Levine, partner at Andreessen Horowitz, phrases it this way:

“I am a huge advocate of the MVP. Having barely lived through the alternative—the uber, world-eating product that never releases—creating a viable yet less grandiose product of value along the path to something larger is a far more prudent approach.”

An MVP:

Tests your product-market fit

Gives you critical, on-the-ground user feedback

Establishes you to your target market as a brand that can provide value

Farmville is a classic MVP success story. Zynga’s philosophy for its development was "Fast, light and right." As soon as they had a “fast, light and right” version, they launched, getting the game into the users’ hands and seeing their reactions. In Farmville’s case, the reaction was amazing, reaching 1 million active users in just six days.

Important: to be minimally viable, your product must contain the top compelling features of your future planned product AND have the highest attention to quality.

In other words, if you can offer fat piglets, your market will realize that you can probably follow through with fat pigs. If you offer scrawny pigs, you just dive-bombed your future chances in that market. That is not a Minimum Viable Pig.

Beyond the MVP: newer approaches

The MVP also has a more recent companion - the MVE (Minimum Viable Experience). This refers to your ability to craft an enjoyable experience for your early customers’ encounter with the MVP. Your MVE takes into consideration that every MVP gets used within the context of your customers lives and it helps this first encounter be a memorable one. The goal of the MVE is to have customers be happy to re-engage with your product and become its early advocates.

Examples of things you can do to create an impactful MVE include additions to your product that make early users feel special, or dedicated success representatives to make sure the early adopters get extra love.

And speaking of love, some proponents of lean development advocate for an MLP (MInimum Lovable Product) rather than just an MVP. The idea when building your MLP is to do what it takes to create an initial offering for your product or service - that people will love from the start, rather than just tolerating it. This approach can be especially important if you are entering a competitive space that already has some viable alternatives on the market. Consumer love or delight is what would then be needed to entice them to engage with something new.

Approach 2: SRP (Sales Ready Product)

MVP is not the only way - or always the most fruitful way - to go. Jim Goetz of Sequoia Capital describes Don Templeton’s pioneering Sales Ready Product approach as a way to compress the sales learning curve, achieve positive sales yield faster and attain a 50% close-rate in 30 days.

An SRP is a product developed and targeted to an extent that the demo itself creates real value for your target customer and immediately inspires a “I NEED this!” feeling.

As Goetz explains the difference between an SRP and an MVP:

“An SRP requires more upfront research and development than an MVP but the results are worth the effort. An MVP may eventually validate product market fit, but only through incremental iteration against the initial idea. An SRP will chart a course towards market leadership, even if initially it takes longer to research and develop.

“If you compare MVP and SRP sales curves, the MVP might launch first. An SRP takes a bit more time because it includes a longer development cycle and beta periods and extensive customer research.

“However, once a company releases an SRP, customer transactions accelerate, sales cycles shorten, and renewals come more quickly, all of which fuel the growth and dominance required to establish market leadership.”

In order to create an SRP, you need to:

Do extensive user research to pinpoint your user’s real pain

Uncover the user objections which could kill your product’s chances and address them first

Be very specific about your target customer - and don’t waste time on prospects that don’t match

Create a demo that uses your customer’s actual data and creates immediate value (they should not need to think about what your product can do for them; it should be “Whoa! I NEED this!” obvious)

If you’re bringing fat pigs to market, your Sales Ready Pig demo should let your user taste some juicy bacon.

Approach 3: Product promise

Maybe you don’t need to go to market with an SRP. Maybe you don’t even need an MVP. Maybe all you need is a promise.

While that sounds like the name of a country western song, it is in fact the approach of Gigi Levy-Weiss of NFX:

“The product promise is, in fact, the first step of finding your product-market fit and testing its validity should be done before putting any effort into building the product. What you are actually testing is that customers respond well, in a measurable manner, to your product concept. You are using language as your building blocks, telling your product’s story the way you would market it, had it already been built.”

The product promise is the go-to-market approach underlying crowdfunding sites like Kickstarter. You tell your product story, take pre-orders, and let your potential customers speak with their wallets.

If not enough voices speak up for your product, you pack up and go home to the drawing board - no time or money wasted on creating MVPs or SRPs.

Bonus approach: The “MVP Promise”

Here’s a bonus approach that combines the MVP and the Product Promise:

Yevgeniy (Jim) Brikman takes the position that MVP is not a product; it is a process.

As he explains it, “When you build a product, you make many assumptions. You assume you know what users are looking for, how the design should work... No matter how good you are, some of your assumptions will be wrong. The problem is, you don't know which ones.”

“Minimum Viable Product” is the process by which you uncover the flaws in your assumptions and course correct - before investing any significant time and resources.

At each stage of your process, ask:

What is my riskiest assumption?

What is the smallest experiment I can do to test this assumption?

Implement, analyze, course correct - and iterate.

This was how Dropbox approached their MVP. Founder Drew Houston created a 5 minute video of himself clicking around his own computer screen and showing how Dropbox worked. The video was aimed at technology early adopters.

What happened? The video drove hundreds of thousands of visitors to their website. Dropbox’s beta waiting list grew from 5,000 to 75,000 overnight.

Dropbox had tested their assumption that people would be interested in a file synchronization service - without the time and resources it would take to build an actual prototype. Now, confident in the market demand, they could start building.

When should you go-to-market?

It’s trite but true that timing is everything when bringing a product to market.

Pete Flint of NFX explains:

“Enter a market too early, no matter how strong the founding team, and you could be stuck waiting for a day that never comes. Enter too late and you’re fighting an uphill battle against incumbents with greater scale.”

The ideal time to go-to-market, says Flint, is when these three preconditions have arrived at the minimum acceptable levels for whatever you are offering:

Economic impetus

Enabling technology

Cultural acceptance

Economic impetus

If your market is blessed with nice quality, inexpensive beef, mutton and venison, this isn’t a great time to bring your fat pig to market. If, on the other hand, there is a surge in the prices of other types of meat, bringing in a more affordable fat pig may speak powerfully to meat-lovers on a budget.

Can your customers pay for your product? Do they have an impetus to pay for your product? If the answer isn’t “YES!” then you don’t have this precondition.

Enabling technology

Let’s suspend reality and say that you’d brought your fat pig to market in a society where they haven’t yet invented sharp knives, all you’d get are blank stares. “We can’t eat that! Don’t you have any roots or berries?”

Voice recognition tech is an enabling technology for virtual assistants such as Alexa or Siri, just as knives are an enabling technology for eating pigs. If you had tried to enter the market with a virtual assistant offering too early, before the technology was really up to supporting its use, you wouldn’t have gotten off the runway before you petered out.

Cultural acceptance

Even if you bring your fat pig in a market with no affordable meat and plenty of knives, if the market is full of religious Jews or Muslims, you’re out of luck. Eating pigs is just not culturally acceptable, and that isn’t likely to change soon.

But sometimes it is a matter of time. For example, lots of people were creeped out by the face recognition tech on phones, before nearly everyone decided, ‘Hey - this is really convenient.”

When these three preconditions are realized for your product, you have a potential tipping point, or as Flint calls it, a critical mass point.

Source: NfX

Virtually every category-defining company in history has entered at just the right time to achieve scale at the critical mass point, asserts Flint.

“This is where the first-mover (or last-mover) advantage paradigm gets it wrong. What’s important isn’t whether you’re earlier or later than your competitors on an absolute basis — rather, it’s all about who enters the market closest to the critical mass point. It’s at this point when technology, economic and cultural forces can combine to enable explosive growth for founders.”

How should you go-to-market?

If you’ve established what you are going to market with, and when you are going to market, now - and only now - should you think about how.

While, as per Ben Horowitz of Andreessen Horowitz (a16z), “Selecting the right channel is critical for any business — and products often fail because the company chose the wrong route to market,” the right channel is a direct outgrowth of what, when… and also who.

As Horowitz puts it, “A properly designed sales channel is a function of the product that you have built and the target — i.e., customers or market — that you wish to pursue.”

Are you selling organic, free-range fat pigs to individuals?

Are you selling passels of fat pigs to sausage factories?

Or are you selling fat pigs to would-be pig farmers, together with providing support as they start on their porcine adventures?

https://giphy.com/gifs/chipotle-good-farm-3o7WINNyOPBUWL0gDu

Each of those cases is going to require a different sales channel to be effective.

In this short whiteboard video, Peter Levine of Andreessen Horowitz shows how the same product might need different routes to market depending on the customer segment:

Source: Andreesen Horowitz

I highly recommend reading Horowitz’s framework and examples in the original, but in the meantime, let’s take a look at a few different issues you might encounter when deciding how to go-to-market.

Top down vs. bottom up

Are you going to start with individual users and work up? Or start with upper management at big organizations and get them to purchase and implement your product across their entire organization?

Mark Cranney of Andreessen Horowitz lays out the differences neatly:

Source: Mark Cranney

New markets

If you’re an innovator who is solving problems people don’t even know they have with a solution that they can’t even conceptualize, you’re in for a tough job.

But it’s not impossible.

In this video, Martin Casado of Andreessen Horowitz reviews the unique challenges and success requirements of market category creation, including:

Investing heavily in the product story

Having a warm body in your target customers’ organizations

Pricing (counterintuitively, you should actually aim high)

Never bundling with a more mature product

Scaling

Go-to-market is going great! It’s time to scale! PAR-TY!

Hold your horses.

Premature scaling is a top cause of startup death, according to Steve Blank. 74% of high growth Internet startups fail due to premature scaling. 93% of startups that scale prematurely never break the $100k revenue per month threshold.

And on the positive side, startups that scale properly grow about 20 times faster than startups that scale prematurely.

If timing is everything for go-to-market, it is at least as true for scaling your go-to-market.

Sarah Wang and David George of Andreessen Horowitz give a concrete example of how to know when you should (and should not) scale your GTM from bottom-up sales to top-down sales:

Source: Andreesen Horowitz

Will you please go (to market) now?

Even if you’re not Marvin K. Mooney, sometimes it’s hard to make that final step and go. But if you’ve answered the what, the when and the how, and the time is right, the time is now. Don’t hang back; get those fat pigs to market and you’ll bring home the bacon.